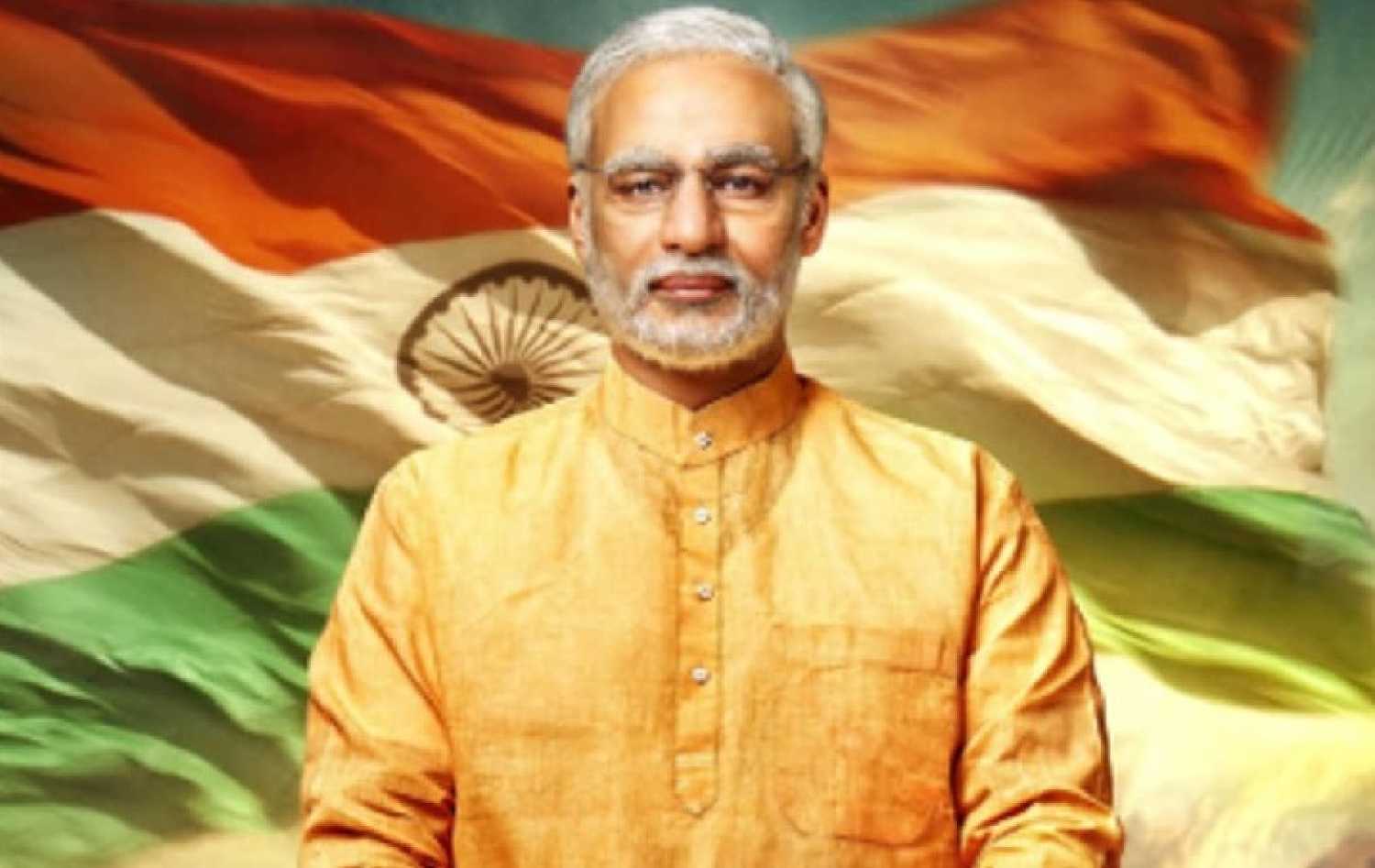

The Omung Kumar film, with Vivek Anand Oberoi playing Narendra Modi, is set for release on 5 April, less than a week before the first phase of polling for the Lok Sabha.

Would PM Narendra Modi fall foul of the Election Commission's model code of conduct?

Mumbai - 19 Mar 2019 18:45 IST

Updated : 23:22 IST

Keyur Seta

Shriram Iyengar

The biopic of India’s prime minister Narendra Modi will now hit the theatres on 5 April. Directed by Omung Kumar, the film, titled PM Narendra Modi, will see Vivek Anand Oberoi playing Modi.

The film was earlier scheduled to be released on 12 April, just a day after the first phase of polling in the seven-phase general election. But on Tuesday, the makers announced that the film's release had been advanced by a week to 5 April.

Biopics in India generally tend to be hagiographic and no one expects the prime minister's life story to be any different, particularly as the film, which has the blessings of the BJP, is being released during the election campaign.

The Election Commission's model code of conduct, or MCC, came into effect earlier this month when the commission announced the dates for the election.

The MCC is meant to ensure a level playing field for all contestants and prevents governments from overtly backing the re-election campaign of their ruling parties. No new projects or policy decisions can be announced or inaugurated when the MCC is in force. Moreover, 48 hours before polling a 'silence period' is enforced when no party is allowed to canvass for voter support, either on the streets, in the print media or on the airwaves.

It is in this context that the release of the biopic and another web-series on Modi could run into trouble as opponents may see them as proxy campaigns in the silence period.

The MCC has been evolved over the years by the Election Commission with the consensus of political parties. Though it is not backed by law, it provides a moral standard to be upheld by all contestants during an election and the commission has the power to disqualify those who transgress its norms.

However, over the years, political parties have exploited loopholes in the code or indulged in sharp practices to ensure visibility during voting. The most famous instance was during the last general election in 2014, when Modi, then the challenger for the prime minister's post, posed for news photographers and cameramen with a lotus emblem. The lotus is the BJP's election symbol.

Given all this background, would the release of a film celebrating the life of one of the prime candidates in the election violate the MCC? Yogendra Yadav, former Aam Aadmi Party leader and currently head of the Swaraj Abhiyan party, simply said, “This is obnoxious, but what else do you expect from this regime?”

Suhas Palshikar, social and political scientist, said, “It violates the model code of conduct. The Election Commission should do something about it.”

Films have been a prominent tool of political propaganda since cinema began to demonstrate its hold on the people. Lenin famously said, “Of all the arts, the most important for us is cinema.” The films of masters such as Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov were used to cement Communist rule in the new-born Soviet Union in the first quarter of the 20th century.

In Hitler’s Third Reich, the infamous propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels used German cinema as a means to propagate Nazi ideology. Leni Riefenstahl’s coverage of the 1936 Berlin Olympics was a case in point.

In India, a recent case in point has been Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019). Made on an estimated budget of Rs28 crore, the film has already grossed over Rs230 crore in a nine-week run. Its run was boosted by the Pulwama suicide bombing of 14 February and the air strikes that followed.

In such an environment, a biopic on an incumbent prime minister being released during the election campaign could conceivably sway emotions, particularly if made in true-blue commercial style.

A prominent earlier example is that of the late J Jayalalithaa, former chief minister of Tamil Nadu, whose hit films with mentor and former chief minister MG Ramachandran would be re-released after the MCC came into effect.

There are several rules that the film and the web-series could run counter to. Key among these are rules that suggest political parties must refrain from ‘any activities or making any statements that would amount to attacks on the personal life of any person or statements that may be malicious or offending decency and morality’ during the run-up to the elections.

The Election Commission in the guidelines posted on its website goes further to state that ‘no aspect of the private life, not connected with public activities, of leaders or workers of other parties shall be criticized. No criticism of other parties or their workers on the basis of unverified allegations or on distortions.’

Another key rule is that for ‘programmes incurring expense to directly promote the electoral prospects of any particular candidate or candidates, prior special authority from the candidate concerned for incurring the expense shall be obtained, in writing, as required under section l7l-H of the Indian Penal Code, and such authorization should be submitted to the district election officer within 48 hours. Any violation should result in action for prosecuting the person concerned.’

The BJP can justifiably say it is not one of the producers of PM Narendra Modi or of the web-series. But while the party has no direct association with the film, party president Amit Shah was scheduled to launch the film's second poster today. That got postponed because of the death of Goa chief minister Manohar Parrikar.

Irrespective of whether the party has anything to do with it, the film remains an effective platform for propagating its programme, given that it is practically impossible to separate Modi from the BJP. This will allow the film to build on the popularity and personality of the prime minister.

As for the party, the advantage lies in the visibility the film may give it. It is likely that the film will use the BJP flag and symbol in some of its visuals. This will help the party to step over the rule that says ‘Advertisement materials must not –

(a) mention the party in government, by name;

(b) directly attack views or actions of others in opposition;

(c) include any party/political symbol or logo or flag;

(d) aim to influence public support for a political party / candidate for election

The consolidated guidelines of the MCC also state that ‘no advertisements shall be issued in electronic and print media highlighting the achievements of the government at the cost of the public exchequer.’

Since neither the party nor the government is connected with the production of the film or the web-series, there is no question of either being made ‘at the cost of the public exchequer’. However, both have the potential to act as subliminal advertisements for the party in power.

Asked about the matter, a senior official of the Election Commission said, “Until and unless we see a complaint, or what the objection is, we cannot say anything.”

However, not everyone buys the contention that the film treads on the right side of an extremely thin line. Chandan Nandy, political analyst and executive editor of the South Asian Monitor, didn’t mince words on the decision of the makers to release the film bang in the middle of the polls. “I think it’s wholly wrong, immoral and unethical," Nandy said in a telephone conversation with Cinestaan.com. "You cannot be doing this because this directly comes under the model code of conduct.”

Nandy believes people’s minds can be affected by political biopics or politically charged films. “You saw that during the controversy of Padmaavat (2018). This [film] certainly has the potential because it is going to come immediately in the backdrop of the air strike on Pakistan, which happened so close to the announcement of the poll dates. It is supposed to have raised the profile of the prime minister. So, this doesn’t augur well for a democratic system. Questions must be raised on the propriety of the Election Commission itself,” he said.

Nandy recalled how in the past, too, films with political content had been released and cited the example of Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975), which was said to have been loosely based on then prime minister Indira Gandhi. However, he believes those were different times.

“I don’t think society was so polarized at that time that it would have made any difference to the elections,” said Nandy. “But here you already have a very polarized society where this administration is trying to take so many uncalled for advantages off non-issues. The question that crops up in my mind is whether the PM and the BJP are so worried that they have to do these kind of things to seek a spike in the PM’s popularity.”