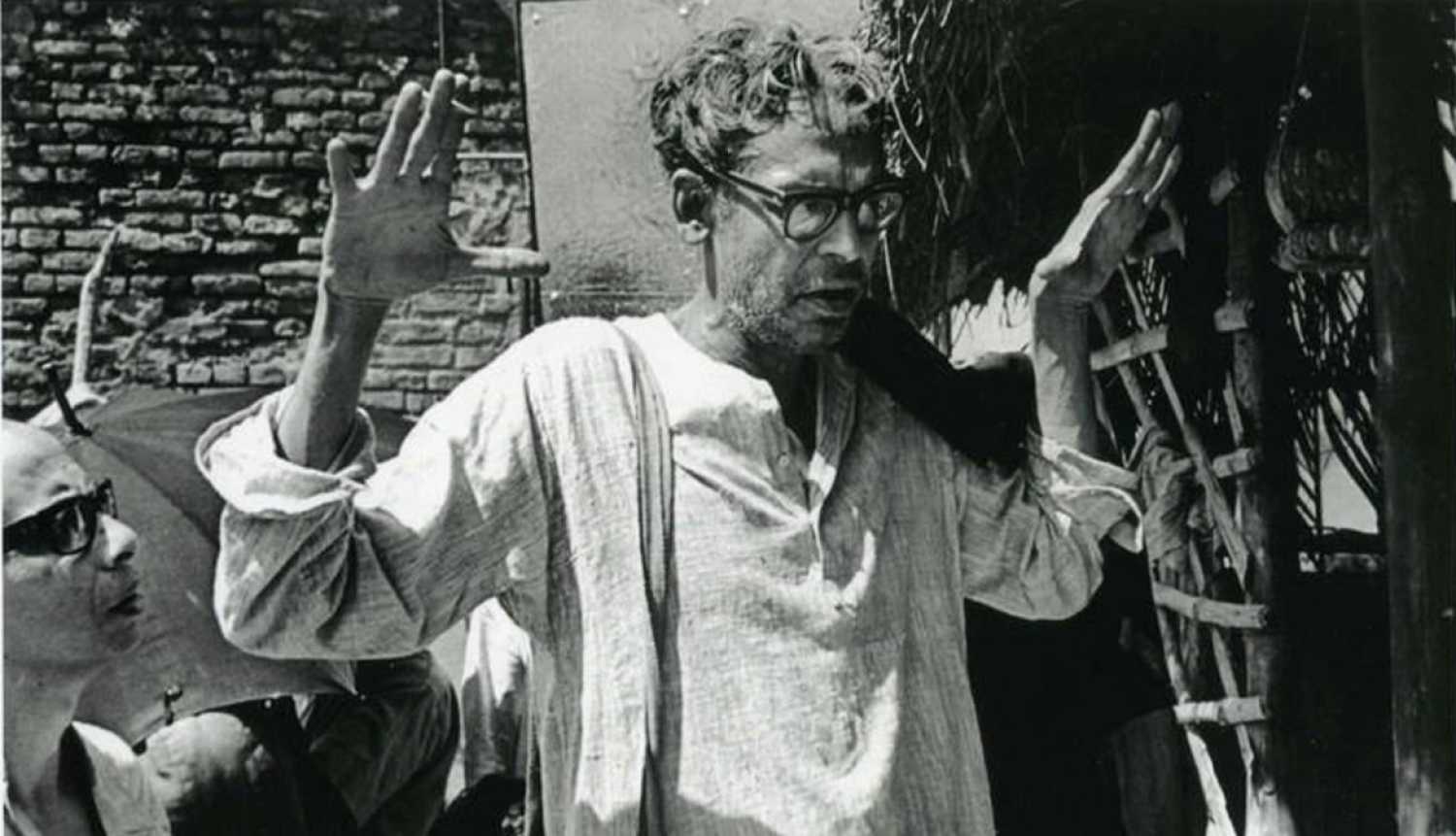

The writer-director, who died a forlorn man on 6 February 1976, wrestled with the splintering of culture and the state of the individual displaced by politics in his films.

Ritwik Ghatak, the eternal refugee – Anniversary special

Kolkata - 06 Feb 2022 23:55 IST

Updated : 07 Feb 2022 0:19 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

Though a tragic victim of the Partition of 1947, Ritwik Ghatak constantly brought a positive and celebratory insight into the personal and national dimensions of homelessness through his cinema. “Exile and homelessness can teach us the joy of living internally as well as externally without boundaries and without borders,” the filmmaker said.

One reason for the growing posthumous critical acclaim and recognition for Ghatak is the courage, power and anger with which he dramatized the urgent modern questions of ‘nationality’, ‘borders’ and ‘exile’.

“It [Partition] does not affect me directly,” he once said in an interview (quoted in Ritwik Ghatak: Cinema and I, Ritwik Memorial Trust, Calcutta, 1987, p80). “It does, in a broader sense, in an indirect way.

“Filmmaking is a question of your subconscious, your feeling of reality. I have tackled the refugee ‘problem’, as you have used the term, not as a refugee problem. To me, it was a shocking splintering of culture.

“During the Partition I hated pretentious people who clamoured about our independence, our freedom. I kept watching what was happening, how the behaviour pattern was changing due to this great betrayal of national liberation. And probably gave vent to what I felt.

“Today, I am not happy and whatever I have seen comes out — consciously or unconsciously — in my films. My films may have been ridden with expressive slogan-mongering or they may be remote. But the cardinal point remains — that I am frustrated by what I see around me; I am tired of it.”

What had Ghatak really ‘seen’ to disturb him so and bring it across in myriad different ways in his films? Haimanti Banerjee in her monograph on Ghatak, published by the National Film Archive of India in Pune in 1985, wrote: ‘At the threshold of 20, Ghatak was witness to the eventfulness of a history which turned its pages virtually every six months. What Ghatak confronted and became aware of was a chronicle of unabashed display of domination and oppression of humanity at large by a handful of owners of power and technological means of suppression.

‘In his perception of such a reality, Ghatak realized that this phenomenon of control was spread all over the world. Nearer home at his doorstep, he saw the enormity of human suffering and privation, but he also witnessed the rise of essential human qualities of courage and heroism. The war of freedom transformed dignity to indignity and dependence to self-determination.’

Ghatak defined Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha (1965) as his trilogy. The three films are bonded as much by the cultural elements of Bengal — theatre, music, poetry and song — as they are by the tragedies of Partition that displaced millions from their roots.

Each family in the three films offers a microcosm of the refugee family, truncated into segments — emotionally and socially. In this sense, it would be safe to conclude that the three films are autobiographical.

The horrific spread of terror consequent to Partition finds expression in Ghatak's statement, "We have all become refugees of our time, having lost the roots of life." This statement is expressed in three different ways in these three films. A press worker in Subarnarekha exclaims: "Refugee! Who is not a refugee?" Ghatak's dream of seeing the two 'Bengals' united comes across movingly through the chanting of the panchali (or prayer book) of the Satyanarain Puja.

Gone were the days of truancy and delinquent rebellion. The crucial period of political unrest and upheaval gave a decisive jolt to Ghatak’s inertia and vacillation. The world was shaken by events that shaped Ghatak as one of the angriest artistes Indian cinema has produced.

Rabindranath Tagore died in 1941. Japanese planes bombed Calcutta on 20 December 1942. In 1943-44, the desperate British, after a series of defeats in Southeast Asia, destroyed all the boats that supplied rice to the villages through an efficient network of navigational canals across Bengal to slow the anticipated Japanese advance.

The government in Bengal looked the other way as the greatest manmade disaster of the time — the Bengal famine — unfolded. Millions of the hungry and the dying left their homes in the villages and trekked to Calcutta crying out “fan chai [give me some rice-starch]” in a desperate attempt to stay alive. Their cries went unheard, leading to the most painful death by starvation for an estimated 15 million people. These were the people who had to bid hurried, panicky goodbyes to their hearth and home, land and sky, neighbours and ties, their roots.

Ghatak was witness to these displaced refugees grimly battling to forge a new life in a hostile environment. His own roots were to lay snapped on the other side of the dividing line — in Dhaka. The anguish of the uprooted, deeply engraved as it was in his mind, was to become an obsession and find recurrent expression in his work.

Heavily influenced by Carl Gustav Jung's views on the role of the 'collective unconscious' and the presence of myth in human affairs, Ghatak believed, according to Bikram Singh in his article ‘A Signature of the Times’, published in Bombay’s The Independent newspaper on 18 December 1987, that the 'essential human truth' would elude the artiste who was disconnected from his moorings. To have access to and imbibe spiritual sustenance from a 'meaningful and precious past', to believe in a personal 'childhood fairy tale', was a basic component of the creative process.

Ghatak remained a refugee in a manner of speaking. He died without finding the identity he was searching for in Calcutta. He was a person displaced from his roots, his soil, and forced to replant himself on what he considered an ‘aberration’. Through his films, one discovers a Calcutta of discontent, a Calcutta of hate, a Calcutta of despair, degradation and dehumanization, a Calcutta of corruption. All this culminated in a Calcutta of anger, of seething fury, and, ironically, a Calcutta of passion, a city that goes on living, loving and hoping; like Binu, who leads Ishwar to a life of hope; like Ishwar who begins to look at life through Binu’s eyes.

Ghatak's involvement with leftist politics in his youth was another influence on his life and work. It resulted in the second uprooting in his life. Too independent and impetuous to toe the party line, he was thrown out. It was a parting that hurt him acutely. But it could not be helped. There was a certain wilful streak in him, and he had to obey, above all, what his own view of the world told him. In this world view, there was place for Marx and Jung, dialectic and dreams, hope and despair, anger and confusion, incandescent creativity and destructive alcoholism.

The three films, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha, dealt with the ravaged psyche of the victims of partitioned Bengal. The three together are regarded as a complex, trend-setting, cinematically splendid trilogy.

Ghatak claimed that Meghe Dhaka Tara was "the greatest of all my films". Most people seem to agree with him. It is a corrosive, complex account of a refugee family with an incredibly stoic protagonist, Nita. According to Ghatak himself, his 'trilogy' was his interpretation of the marriage of the two Bengals.

"When I began making Meghe Dhaka Tara, I did not speak about the political union of the two Bengals. I do not seek to do this even today," he was quoted as saying by Probir Mitra in the article ‘Bohumatrik Meghe Dhaka Tara’ in a special issue of Patabhoomi, literary journal of the Asansol Film Study Circle, in May 2000. "I know that it is difficult to reverse history. It is not my responsibility either. My greatest pain sprung from the politics, the economics and other things that deter the cultural union of these two forcibly divided states. It is this cultural union I have spoken about quite clearly in Komal Gandhar. The same applies to Meghe Dhaka Tara and to Subarnarekha."

Ritwik Ghatak died an ignominious, tragic and painful death on 6 February 1976. Two years after playing out his own death by police bullets in Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974), the filmmaker died in Calcutta’s SSKM hospital, much like Bengal’s rebellious creative artistes Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the poet, Pramathesh Barua, filmmaker and actor, and Manik Bandopadhyay, the classic litterateur.

Like the mythical phoenix, he was consigned to flames, not knowing that he was destined to rise from its ashes. Till today, he remains the stormy petrel of Indian cinema. He hit cinema in India like a tornado, and disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared. His films got international attention only after his death. Things other than cinema that he was involved with, in different phases of his life, also began to emerge.

Before his entry into films, Ghatak was involved with theatre as an actor-activist. He wrote, too, short stories, essays and plays in Bengali and in English. Like all Bengalis of his time, Ritwik Ghatak could not escape the heritage of a phase of self-indulgence into poetry, into prose and into an ideological stand that was markedly leftist. "The ideological base of my work is fundamentally Marxism,” he said.

Shoma A Chatterji has written a book on Ritwik Ghatak's cinema titled Ritwik Ghatak: The Celluloid Rebel.