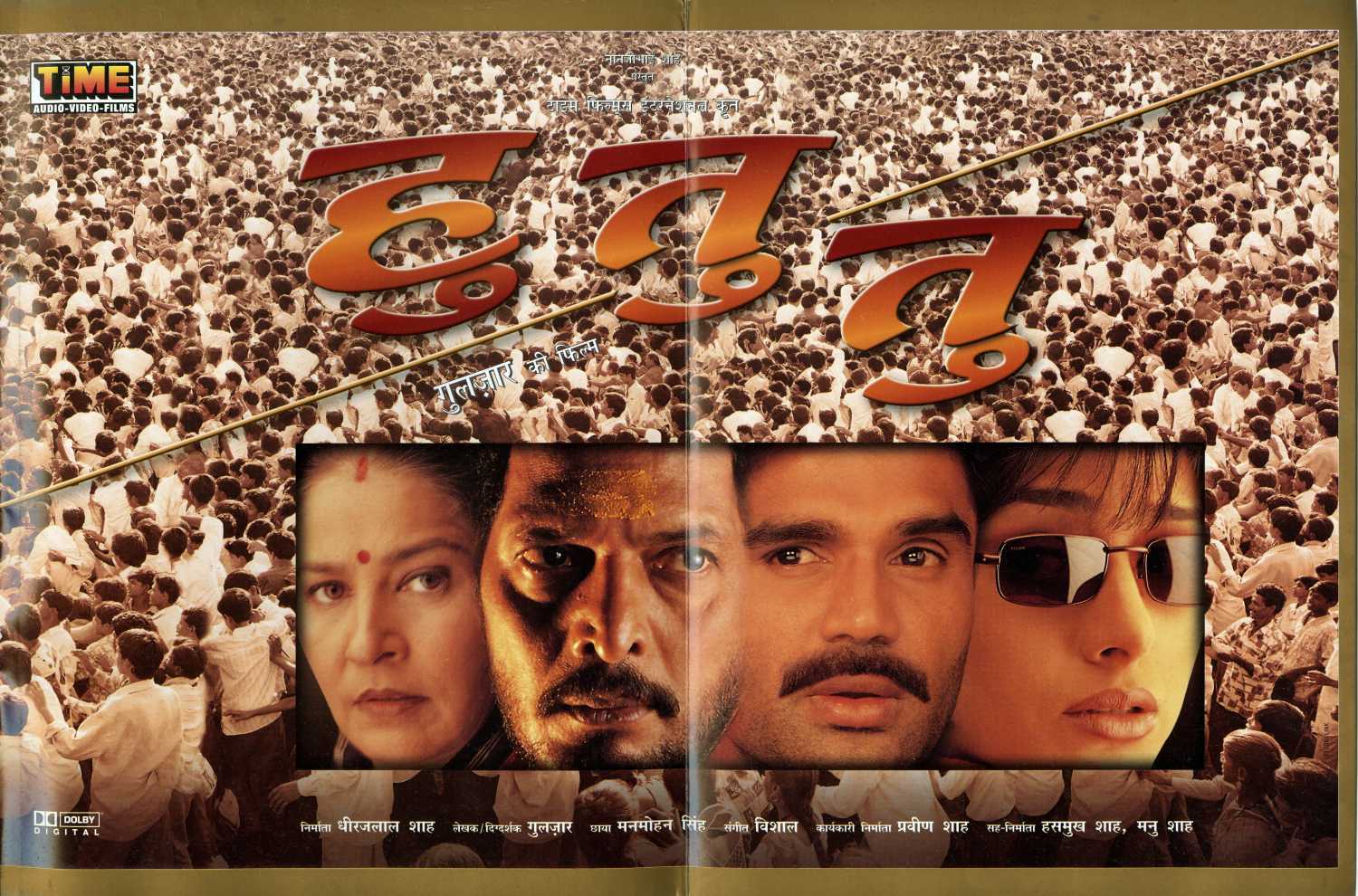

Twenty years ago to the day, Gulzar brought Tabu, Suniel Shetty and Nana Patekar together for a didactic film on political corruption. We look at what went wrong.

20 years of Hu Tu Tu: Gulzar's political diatribe that failed to fire the imagination

Mumbai - 22 Jan 2019 7:00 IST

Shriram Iyengar

On 17 January 2016, Rohit Vemula, a PhD student at the University of Hyderabad, committed suicide after being suspended for "raising issues". The death sparked a movement, perhaps the most important one in the past decade, for the rights of Dalits.

The repercussions of the movement were also reflected in some of the cinema that followed. Pa Ranjith’s fairly commercial Kaala (2018) and Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal (2018) are the obvious examples. But in 1999, Gulzar attempted something similar, with very different results.

To be sure, to use Gulzar as an example of a director projecting subaltern stories could well be dismissed as privileged bias. The filmmaker’s Hu Tu Tu (1999) was released in the penultimate year of the second millennium, when such subjects were far away from popular conversations. The film was based on a short story of Gulzar’s and dealt with the oldest strategy in Indian politics — the politics of hate.

The story revolves around the game politics plays in the life of a family. Panna (Tabu) is the daughter of the powerful politican Malti (Suhasini Mulay), who is not averse to junking her family in her pursuit of power. In her way is a new revolution led by Aditya (Suniel Shetty), the disenchanted son of an industrialist, who is inspired by street poet Bhau (Nana Patekar).

The film has elements from several Gulzar films like Mere Apne (1971), Aandhi (1975) and Maachis (1996). But what makes Hu Tu Tu special is Tabu's presence. Though she was still in her more commercial phase, the film revolves around the rebellious Panna played through the actress’s expressive eyes.

The political voice of the film comes through the voice of the oppressed, the sutradhar, played by Patekar. While Patekar has played the role before (most notably in Krantiveer, 1994), it is Gulzar’s poems, composed by Vishal Bhardwaj, that add a new dimension to the political rebel.

It is in Bhau that the Dalit representation finds voice in Gulzar’s film. A wanderer, his voice against those in power is taken as an instance of extremism. He is shunted out, like Vemula, as a threat to ‘civil society’, a convenient excuse for those in power.

The politics permeates through the songs and poetry more than the dialogues in the film. At times, lines like "politics feels like smoke in my blood" seem overly abstract, while the songs feel like direct statements.

The filmmaker uses the tactic of politically powered songs to underline their impact. While it was used partially in films like Mere Apne with ‘Haalchaal theek thaak hai’, and Aandhi in ‘Salaam Keejiye’, Hu Tu Tu’s sutradhar uses songs to outline every key act of oppression.

Whether it is ‘Ghapla Hai’ or ‘Bandobast Hai’, the lyrics depict an existentialist crisis among voters about the political system.

The year 1999 was also a pivotal moment when coalitions truly took hold of India’s political imagination. The fall of the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led National Democratic Alliance government took place later that year, but it was to set the tone for future elections that depended greatly on compromised coalition politics.

Even in the very playful ‘Nikla Neem Ke Tale Se Nikla’, Gulzar’s communism emerges from the shadows. He was, after all, mentored by Shailendra, the lyricist for the man on the street.

‘Worker hai / Vardi pe dhabbe hain tel ke / Kaarkhaane se nikla’ goes a line in the middle of the song.

In addition to the evident call for revolution, the film captures the subtext of an oppressed people fighting for their rights. Bhau represents the landless labourers, the tribals whose forest lands have been given over for the latest infrastructure project.

“I am the best bhangi [pejorative term for a manual scavenger] in my village,” he tells Panna as she comes to visit while he cleans a path to his toilet. These elements of subtext manage to expand the film’s protest from mere anti-corruption to something bigger.

Sadly, the over-long emphasis on politics is also the film’s downfall. While it has some very subtle but effective performances by Tabu and Mulay, the film’s runtime of over two hours goes against it. The often abstract dialogues, meandering screenplay and some substandard performances go against the film's core.

Inevitably, the film bombed at the box office. Circa 1999 was a year of romantic utopia with films like Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, Hum Saath-Saath Hain, Mast and Mann leading the way at the box office. A sardonic and lengthy political essay was unlikely to last.