Kaagaz Ke Phool, which was released on 2 January 1959, has strong autobiographical elements and is almost like a celluloid elegy.

60 years of Kaagaz Ke Phool: The most outstanding self-reflexive film of Indian cinema

Kolkata - 02 Jan 2019 22:43 IST

Shoma A Chatterji

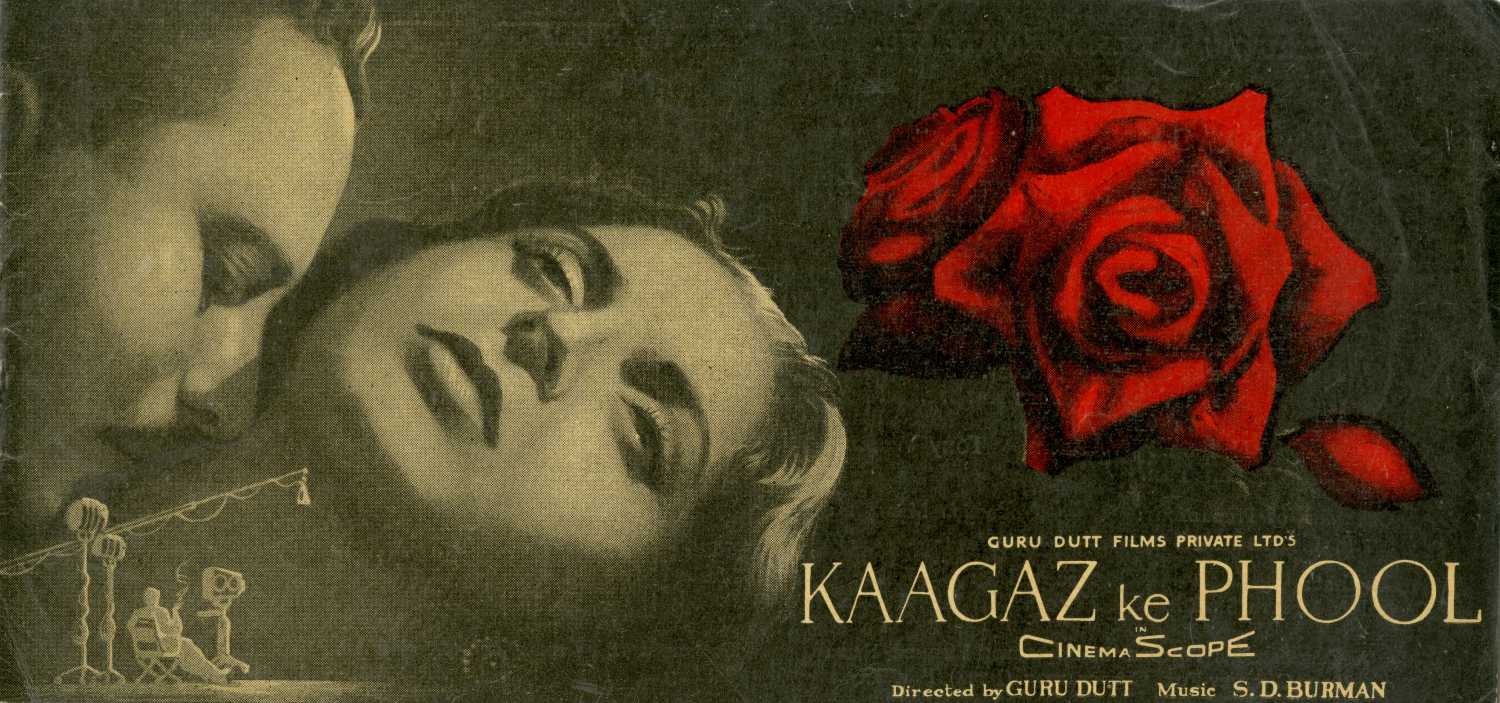

Of Guru Dutt's entire directorial repertoire, Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), or Paper Flowers, was the biggest flop. His ambition of making India's first Cinemascope film ended in disaster.

Sixty years on, Kaagaz Ke Phool is an iconic film that any student of cinema would label a model lesson in filmmaking. The film lends itself to multiple readings of the text, and even then there might be areas that remain invisible, waiting to be ‘discovered’ by some other enthusiast.

The world of cinema is a narcissistic one. Filmmakers tend to get sucked into this world and, at one time or another, use the paraphernalia within filmmaking, the infrastructure that is sustained within the studio ambience, clips from other films, in their own work.

Sometimes, like Guru Dutt has done brilliantly in Kaagaz Ke Phool, a film can embrace even the nuances that evolve in relationships between cinematographer and director, or between director and leading lady, or director and writer. Each such nuance, subtle or pronounced, can emerge as an independent space of inquiry.

Self-referential films offer different aspects of cinema such as filmmaking [Kaagaz Ke Phool, Samar (1999)], movie stars [Sone Ki Chidiya (1958), Bhumika (1977), Rangeela (1995), Akele Hum Akele Tum (1995), Halla Bol (2008), Billu (2009), Heroine(2012)], institutions of the industry [Guddi (1971), Zubeidaa (2001), Khoya Khoya Chand (2007), Luck By Chance (2009)], movie theatres [Akele Hum Akele Tum, Traffic Signal (2007)], a film being shot on location or in the studios [Bade Miyan Chhote Miyan (1998), Samar], the audience [Mast (1999), Fan (2016)], one special film [Darmiyaan (1997), Guddi], etc.

But unlike Kieslowski’s Camera Buff (1979), or Guru Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool, for most filmmakers, a film-within-a-film need not be autobiographical. The audience gets an insight into cinema as an art form, as science and technology, as a mirror to society, or as cinema that reflects social concern and is a tool of self-expression for the filmmaker, a creative artiste.

Most filmmakers, wittingly or otherwise, tend to make at least one self-reflexive film-within-a-film at some time. Most Indian filmmakers use this style to explore the psyche of people involved in films, the jugglery that goes on, the stakes involved in changing lives and lifestyles, and, more importantly, to involve the audience in this politics of representation.

Cinema-within-cinema also draws the attention of the spectator to filmic codes, eg camera angles, montage, colour, music, sound, and so on. The presence of cinematic items, objects and other paraphernalia, such as the movie camera, the boom, the lights, the makeup, the costumes, the makeup room, huge posters of films and stars, the back office of a studio classify a self-reflexive film into a special genre.

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959) is one of the most moving self-reflexive films made in India. It is a fine and subtle tribute to the glory days of the studio era, using its history from about the 1930s to the 1940s as its backdrop.

The film tracks the introspective and retrospective journeys of Suresh Sinha, a once celebrated director who is now going through a bad patch, both professionally and personally. He is estranged from his wife and daughter, while Shanti, the leading lady whom he had groomed to fame and glory, and then fallen in love with, has drifted away.

Suresh Sinha discovers that the studio floors are his last recourse and seeks refuge there, tracing back his journey. He finally comes to terms with the reality that fame and success are as ephemeral as life itself. By then, however, it is too late.

Kaagaz Ke Phool has strong autobiographical elements. It is almost like a celluloid elegy. Guru Dutt wrote for himself with his screenplay, his images, his music and his lyrical pacing of the film. He is said to have had an intense relationship with Waheeda Rehman, one of his leading ladies, as shown in the film. This brought about phases of estrangement with his wife Geeta Dutt from time to time.

He began to drink when he was not working. He suffered from long periods of depression. He became a chronic insomniac. In fact, Bimal Mitra, the original author of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), wrote an entire non-fiction book entitled Binidra in Bengali, meaning The Sleepless One, that described his close relationship with Guru Dutt during his long phase of insomnia as they discussed the strategy to turn the novel into a film.

It is said that Guru Dutt's premature death by suicide was foreshadowed in the film. Strangely, however, one finds that Shanti functions as the sacrificing woman who falls desperately in love with him but fails to rescue him from a tragic death. Suresh Sinha is in love with Shanti the actress, not Shanti the woman. Waheeda Rehman stepped out of her mentor's life to perform some of the best roles of her career in Guide (1965), Khamoshi (1969) and Lamhe (1991). Yet, they never express their love in so many words right through the film.

Kaagaz Ke Phool uses the studio era from about the 1930s to the 1940s as its backdrop. An early shot reveals Suresh leaning from the balcony of a cinema hall where Vidyapati (1937), an unforgettable musical romance, is playing to a full house. The films Suresh is shown making or having made are films that actually exist in the annals of Indian cinema.

Guru Dutt weaves his film-within-a-film story of Kaagaz Ke Phool with Devdas, which is the film being directed by Suresh. He manages to persuade his producer to cast Shanti, an orphan girl he had met one day when she walked on to the sets within the camera frame, to play Parvati. The entire subtext happens in a series of coincidences and accidents. Not once does one get to see Devdas being actually shot in this film. But there is this strong sense of intercutting between Devdas and Suresh with Suresh taking to the bottle and losing out on life, family and love.

Towards the end of the film, the only retreat for Suresh is the studio where he shot many successful films. Here, with his cameras, his arc lamps, his backdrops, his sets, his technicians and his artistes, he can create and control his own world of make-believe and beauty.

But this space grants him only the metaphorical consolation of a fictive universe. When he loses his favourite actress in this space, and his daughter in court, he takes to drink, as if with a vengeance, and becomes homeless. He returns to the space all over again after having lost his family, his career and his audience.

'By now, he defines the space as an indoor space that has evolved into a private sepulchre for himself,' wrote Nasreen Munni Kabeer in Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema, 1997.

Raminder Kaur and Ajay J Sinha (Bollywood: Popular Indian Cinema Through a Transnational Lens, Sage, 13 July 2005) wrote: 'Kaagaz Ke Phool may well be seen as the high point of the artistic collaboration between Guru Dutt and the cinematographer VK Murthy. As a film about the film industry and largely set within the locale of a film studio, it allowed for elaborate set pieces that capitalized on a ‘behind-the-scenes’ atmosphere of movie-making. However, it has been suggested that this elaborately self-reflexive sensibility is precisely what was responsible for the film’s inability to find commercial success.'

Guru Dutt actually asked two of his cinematographers, his earlier one, V Ratra, and his current one, VK Murthy, to appear in person as camera persons within the film! Murthy would fondly recall the film as Guru Dutt’s gift to his (Murthy’s) craft. Being the first Cinemascope film in India, it was a definite technical challenge and the nature of the narrative itself demanded a certain experimentation with light in all its aspects (Raminder Kaur and Ajay J Sinha).

The authors noted that the behind-the-scenes realities of filmmaking define the mystique of cinema that is better kept away from the actual film than to allow the technical and other private and personal relationships to tumble out of the cupboard that hides lots of skeletons. This exposure of the mystique that cinema keeps away from the audience may have led to the failure of this film.

Guru Dutt’s suicide in 1964, five years after the debacle of Kaagaz Ke Phool, was foreshadowed through Suresh Sinha’s death at the end of the film when he reclines, wearily, on the chair of the spacious but empty studio floor, lit strategically and magically by Murthy’s amazing capacity to turn the camera into a character.

Suresh Sinha’s death is also a kind of metaphorical suicide marking his death in the place he was passionately in love with and could not live without. The studio floors with the cranes, the microphones, the paraphernalia create a parallel world within the larger world he inhabits, content only when shooting or giving directions or whatever.

The other world, the one where his wife is estranged, daughter is in boarding school, Shanti is slowly losing her sanity and escaping through knitting, knitting and knitting, smoothly blends into the parallel world of filmmaking so far as Suresh is concerned. This leaves you guessing, which was the world he truly inhabited? The world of arc lights, booms, technicians, and so on? Or the ordinary world of unhappy husband, father and lover all rolled into one?

The song, 'Waqt ne kiya kya haseen sitam, tum rahe na tum, hum rahe na hum [O the wonderful tyranny of time, you are no longer yourself, nor have I escaped unscathed]', penned by Kaifi Azmi, composed by SD Burman and sung by the lilting voice of Geeta Dutt, says it all. Or, Rafi’s unforgettable 'Bichhade sabhi baari baari [One by one, everyone has left]' which lays out the creative artiste’s sentimentalism that ends in tragedy, both as a creative artiste and as a man who loved and lost because he could not face up to the tragedy of his life.

Was he an escapist and a failure like Devdas whom he paid such great tribute to? Or was it his creative arrogance on overdrive? Was Kaagaz Ke Phool an attempt to show the dark truths that lie behind the glitter and gloss of stardom and the creative romanticized mindset of the director? Was it a sad pointer to the creative artiste having run out of ideas? Or was it a critique of oneself?